|

|

Iceland:Physical and Psychological Space

Nature's Calling: The Dyeing Season

Textile Crafts:Icelandic Textile Center, Vatnsdæla Tapestry and Cultural Identit

Fish Tanning and Icelandic Wool:Living Cultures, Natural Resources and Traditional Knowhow

|

Iceland: Physical and Psychological Space

16th July 2023

I spent July 2015 at The Icelandic Textile Centre at a seaside Northwestern town of Blönduós, Iceland. The aim of the residency was to experience how solitude relates or impacts my art practice. I was creating art in my studio in an industrial building located in Fo Tan, an industrial area in Hong Kong prior to the residency. Moreover, my life in Hong Kong was often hectically busy (I believe many artists and creators can relate).

Time

I constantly experienced a shortage of time in my day-to-day life, rushing from here to there, too busy to create and complete artworks. What if I have unlimited time? Would I be more productive? Would I be able to be still and decompose ideas? Would I learn to take it slow?

I arrived in Iceland in the last few days of May and experienced the Midnight sun, where the sun sets close to the horizon and rises after midnight, leaving the sky in shades of red, lilac and pink.

Time

I constantly experienced a shortage of time in my day-to-day life, rushing from here to there, too busy to create and complete artworks. What if I have unlimited time? Would I be more productive? Would I be able to be still and decompose ideas? Would I learn to take it slow?

I arrived in Iceland in the last few days of May and experienced the Midnight sun, where the sun sets close to the horizon and rises after midnight, leaving the sky in shades of red, lilac and pink.

During my month-long residency, day time lasted for 20 to 22 hours per day. Blackout curtains were set up in my room, but my experience of time altered. First, my body was confused and tired. My body was awake for longer hours due to the long exposure to sunlight, but my energy was not sufficient to be continuously active. Therefore, I was mostly awake but tired. Secondly, my psychological experience of time was loosen, when the passage of time was easily unnoticed due to the back of changes throughout the day, time became a deconstructed concept, broken into fragmentised presents. One could easily procrastinate as there seems to never be ‘too late’ for the tasks. Everyday was an eternal morning or afternoon.

I then gradually measure the passage of time through progress, the area of embroidery done, the amount of dyeing process repeated, and the length of loom weaving completed. Instead of being too busy to create art, I reconstructed my relation to time through my art practice.

I then gradually measure the passage of time through progress, the area of embroidery done, the amount of dyeing process repeated, and the length of loom weaving completed. Instead of being too busy to create art, I reconstructed my relation to time through my art practice.

Space

I was unrestricted to studio spaces and was free to explore the landscape in Blönduós and nearby towns. It was a remarkable experience hiking on a mountain in Blönduós, where the sky and natural landscape seems to be boundless. I found myself within an infinite space.

Art Making

I embroidered a world map with white thread on pale oyster gray, the low contrast illustrated an almost borderless map, minimizing and blurring differentiation between nations.

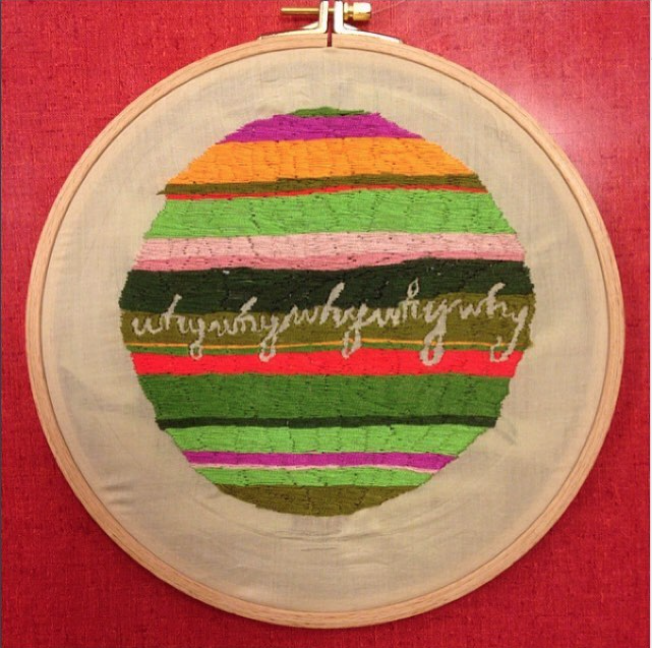

I started taking photos of landscape and nature during my daily walks and unpacking the colours seen in each frame, flowers blooming on fresh green fields, gloomy clouds on a rainy day, a majestic sunset with penetrating rays of red. I completed A Traveler’s quote, a set of 7 embroidery pieces, inspired by the colours from the photos. The quote embroidered was extracted from the movie The Legend of 1900 (1998), where the protagonist questions motives and meanings of traveling after observing many crossing the Atlantic Ocean for vocation.

I was unrestricted to studio spaces and was free to explore the landscape in Blönduós and nearby towns. It was a remarkable experience hiking on a mountain in Blönduós, where the sky and natural landscape seems to be boundless. I found myself within an infinite space.

Art Making

I embroidered a world map with white thread on pale oyster gray, the low contrast illustrated an almost borderless map, minimizing and blurring differentiation between nations.

I started taking photos of landscape and nature during my daily walks and unpacking the colours seen in each frame, flowers blooming on fresh green fields, gloomy clouds on a rainy day, a majestic sunset with penetrating rays of red. I completed A Traveler’s quote, a set of 7 embroidery pieces, inspired by the colours from the photos. The quote embroidered was extracted from the movie The Legend of 1900 (1998), where the protagonist questions motives and meanings of traveling after observing many crossing the Atlantic Ocean for vocation.

“...Why why, why, why, why, why? I think land people waste a lot of time wondering why? Winter comes, you wish it was summer. Summer comes, you live in dread of winter. That's why we never tire of traveling.”

I felt entrapped in my environment and circumstances that restricted my creativity. By going to an unknown place, I longed for adventure and roam for freedom. I pardoned the act of leaving a comfort zone, entering a new environment, seeking internal renewal through external change of environment. Instead of bringing my custom habit and practice with me, emotions and thoughts within me, I was liberated from the self that I loathed or bored. I was not trapped by the environment I was in, I was tired of the version of me in that environment.

Perhaps it was not the new landscape nor a strange season that I was after, but a sense of distance from my old self, so I can review and reflect on myself detachedly. I was longing for an alternative, a possibility of a reimagined self. It was the change of scenery that made clear a change of identity. The land people addressed in The Legend of 1900, were not chasing a warmer or mild weather, but were chasing the absent. The act of pursuing was addictive to distract one from one’s void. In the vastness of space and infinite time, I learn to calmly face and be still with my void.

I felt entrapped in my environment and circumstances that restricted my creativity. By going to an unknown place, I longed for adventure and roam for freedom. I pardoned the act of leaving a comfort zone, entering a new environment, seeking internal renewal through external change of environment. Instead of bringing my custom habit and practice with me, emotions and thoughts within me, I was liberated from the self that I loathed or bored. I was not trapped by the environment I was in, I was tired of the version of me in that environment.

Perhaps it was not the new landscape nor a strange season that I was after, but a sense of distance from my old self, so I can review and reflect on myself detachedly. I was longing for an alternative, a possibility of a reimagined self. It was the change of scenery that made clear a change of identity. The land people addressed in The Legend of 1900, were not chasing a warmer or mild weather, but were chasing the absent. The act of pursuing was addictive to distract one from one’s void. In the vastness of space and infinite time, I learn to calmly face and be still with my void.

Nature's Calling: The Dyeing Season

23th July 2023

I arrived by the end of June and started my artist residency on 1st July till the end of the month. It was still chilly in the Icelandic Summer, but I am from a tropical city after all. Looking out to the then green mountains around the Textile Centre, the artists who stayed in June told me there was no dyeable vegetation in June, the mountain was rocky and empty. The weather warmed up in the last week of June and all plants grew as if the earth was awakened.

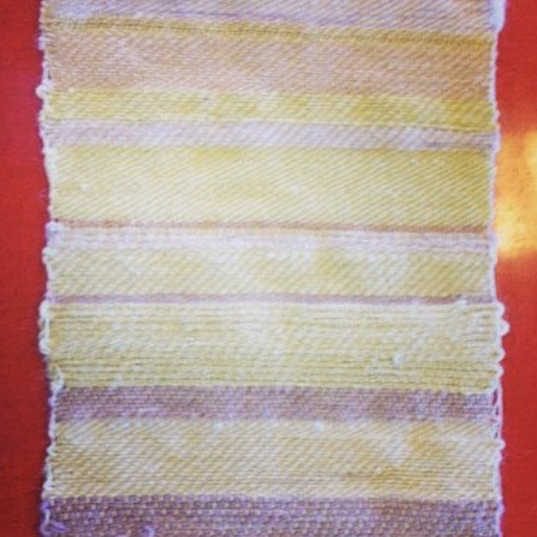

Then like a toddler, I learned the speech of natural dye. I learned to dye with all natural pigments in the dyeing lab, indigo, cochineal. I was taught to recognise and severate plants for dye, rhubarb, flowers, . I then spent my stay experimenting dyeing with different parts of the plant, flowers, leaves, stem, roots. I started a swatch notebook to record the process. I learnt to examine the process of dyeing, changing temperature, time, and amount of dying object, adding a combination of chemicals. I then experiment with dyeing different materials, cotton, linear, wool; yarn, thread, fabrics. I wove the materials into tapestries on a loop and table frame.

In the process, I learnt to appreciate nature and was humbled by the nature’s calendar. Let go of control and go with the flow, you can’t force the flowers to bloom or leaves to grow.

In the process, I learnt to appreciate nature and was humbled by the nature’s calendar. Let go of control and go with the flow, you can’t force the flowers to bloom or leaves to grow.

Textile Crafts: Icelandic Textile Center, Vatnsdæla Tapestry and Cultural Identity

30th July 2023

The Textile Center

The Textile Center lies within the Women's School of Blönduós. A new school promptly replaced the original building that was lost in a fire in 1911 and continued until 1978 when the school's activities ceased. The Textile Center emerged from the union of the Textile Center of Iceland (founded in 2005) and the Knowledge Center in Blönduós (founded in 2012). It stands tall today with a mission to be an international nucleus for intensive research and development in textile production, arts, and craftsmanship. Notably, the center also offers facilities for university studies and adult education, providing access to teleconferencing equipment and examination facilities in collaboration with esteemed universities and lifelong learning centers.

The Textile Center lies within the Women's School of Blönduós. A new school promptly replaced the original building that was lost in a fire in 1911 and continued until 1978 when the school's activities ceased. The Textile Center emerged from the union of the Textile Center of Iceland (founded in 2005) and the Knowledge Center in Blönduós (founded in 2012). It stands tall today with a mission to be an international nucleus for intensive research and development in textile production, arts, and craftsmanship. Notably, the center also offers facilities for university studies and adult education, providing access to teleconferencing equipment and examination facilities in collaboration with esteemed universities and lifelong learning centers.

The Vatnsdæla Tapestry Project

At the Icelandic Textile Centre, a collaboration with the textile museum comes to life through the Vatnsdæla Tapestry Project. Guided by Jóhanna E. Pálmadóttir, this project draws inspiration from the illustrious 11th Century Bayeux-tapestry of France. The project aims to rekindle the Vatnsdæla saga, preserving the ancient art of embroidery while infusing it with a contemporary twist that speaks of picturesque conflicts. Stretching an impressive 46 meters, this tapestry beckons visitors to actively participate in its creation. Delicate hand-spun Icelandic wool becomes the canvas for their artistic expression, weaving them into a rich historical tapestry.

At the Icelandic Textile Centre, a collaboration with the textile museum comes to life through the Vatnsdæla Tapestry Project. Guided by Jóhanna E. Pálmadóttir, this project draws inspiration from the illustrious 11th Century Bayeux-tapestry of France. The project aims to rekindle the Vatnsdæla saga, preserving the ancient art of embroidery while infusing it with a contemporary twist that speaks of picturesque conflicts. Stretching an impressive 46 meters, this tapestry beckons visitors to actively participate in its creation. Delicate hand-spun Icelandic wool becomes the canvas for their artistic expression, weaving them into a rich historical tapestry.

Textile and Cultural Identity through Time

Icelandic narratives and memories intertwine and are celebrated through the millennium-old tradition of spinning and weaving wool. Embroidery patterns inspired by floral and the nature of clothing are believed to hold protective power over the wearer against physical and spiritual dangers. Beyond beauty and adornment, ancient weaving patterns also hold the wisdom of traditional medicine, passing knowledge of herbs, leaves, teas, and natural dyes. The embroidered clothing acts as both armor and natural science textbooks. Along with the calming rhythm of the weaving loom, ancient Icelandic stories, songs and poems were created to pass along the craft and art of weaving from the 13th century. These oral heritage are preserved, guiding weavers in their creative journey.

“These old poems and songs are mostly from the time we wove on the warp-weighted looms, and we have several teaching poems from the 13th, 16th and 17th centuries – like Darraðarljóð or Króksbragur,” explains artist and educator Ragnheiður. “They describe how to weave on the looms, how to fix a broken thread and so on. [W]e used to teach children through songs and poems because back then people didn’t write things down. Icelandic rhymes are full of textiles.”

I had a glimpse of how contemporary Icelandic textile practices threats through traditions and customs. It is a tactile art form immense with story, memory and nostalgia, through touch, sound, smell, temperature, humidity. The present and future of the art form are closely knitted with the intergenerational past.

Icelandic narratives and memories intertwine and are celebrated through the millennium-old tradition of spinning and weaving wool. Embroidery patterns inspired by floral and the nature of clothing are believed to hold protective power over the wearer against physical and spiritual dangers. Beyond beauty and adornment, ancient weaving patterns also hold the wisdom of traditional medicine, passing knowledge of herbs, leaves, teas, and natural dyes. The embroidered clothing acts as both armor and natural science textbooks. Along with the calming rhythm of the weaving loom, ancient Icelandic stories, songs and poems were created to pass along the craft and art of weaving from the 13th century. These oral heritage are preserved, guiding weavers in their creative journey.

“These old poems and songs are mostly from the time we wove on the warp-weighted looms, and we have several teaching poems from the 13th, 16th and 17th centuries – like Darraðarljóð or Króksbragur,” explains artist and educator Ragnheiður. “They describe how to weave on the looms, how to fix a broken thread and so on. [W]e used to teach children through songs and poems because back then people didn’t write things down. Icelandic rhymes are full of textiles.”

I had a glimpse of how contemporary Icelandic textile practices threats through traditions and customs. It is a tactile art form immense with story, memory and nostalgia, through touch, sound, smell, temperature, humidity. The present and future of the art form are closely knitted with the intergenerational past.

Fish Tanning and Icelandic Wool: Living Cultures, Natural Resources and Traditional Knowhow

2nd August 2023

The intricate interplay between environmental cultures and traditional living has shaped the identity of the Arctic people since ancient Norse settlers first arrived on the island. Through a deep bond with their surroundings, these indigenous communities harnessed local resources, cultivating a way of life intertwined with the rhythms of nature. Rooted in the fabric of their existence, Arctic inhabitants relied on fishing and hunting, adapting to their environment with a resourceful and economical approach. This connection between cultural identity and sustainable crafts is exemplified in two Icelandic creative craft industries: fish tanning and the Icelandic wool.

Fish Tanning: Sustaining Wisdom from the Sea

“From the extraordinary Lyngbakur—a fishermen-eating whale giant that disguises himself as an island.” (Folklore in Iceland, Magnús Ólafsson)

For centuries, indigenous Icelanders have thrived in harmony with the sea, practicing sustainable fishing ingrained in their cultural heritage. Every part of the fish is valued, and fish skin, a byproduct of the food industry, finds purpose as clothing that protects against harsh weather and spiritual forces. These skins, adorned with protective and pleasing patterns shield the wearer from evil spirits. The traditional designers and seamstresses are believed to harbor a unique craftsmanship, bridging the seen and unseen realms. Fish skin, remarkably lightweight, durable, waterproof, and insulating, has been fashioned into coats safeguarding against Arctic climatic challenges. Fish skins coats were used as everyday indoor garments, whereas several coats were worn at once or over furs as protection against wind and moisture as outdoor garments.

|

Iceland's fishing and aquaculture sector, a key contributor to the economy, produced 1.3 million tonnes of fish with a value of USD 1327.4 million and provided over 4000 jobs.

“Humans worldwide consumed a little under 150 million tons of fileted fish in 2015. One ton of fileted fish amounts to 40 kilograms of fish skin, and so in that year alone, the industry produced about six million tons of skins that could have been recycled.” (Hakai Magazine, 2015)

|

Resonating the principles of circular economy, the tannery Sjávarleður, or Atlantic Leather located at the seaside town Sauðárkrókur, is a unique establishment transforming discarded fish skin into exquisite leather. Icelanders have practiced traditional fish skin dyeing for centuries, fish tanning was developed and practiced since the 12th century. Tanning plays an important role in the country’s culture: girls were told that the quality of the first pair of leather shoes they sewed would foretell the quality of their marriages.

The fish leather, fashioned into a spectrum of 4000 colors, serves as a resilient alternative to exotic animal skins. Chemical treatments and dyeing processes transform discarded fish skin into an environmentally friendly material, surpassing traditional leather in durability. The animist philosophy of Arctic cultures perceives humans as an integral part of nature, fostering a profound respect for all species. Indigenous practices, rooted in harmony with nature, ensured responsible harvesting of fish populations, echoing a holistic ethos.

The fish leather, fashioned into a spectrum of 4000 colors, serves as a resilient alternative to exotic animal skins. Chemical treatments and dyeing processes transform discarded fish skin into an environmentally friendly material, surpassing traditional leather in durability. The animist philosophy of Arctic cultures perceives humans as an integral part of nature, fostering a profound respect for all species. Indigenous practices, rooted in harmony with nature, ensured responsible harvesting of fish populations, echoing a holistic ethos.

“Spotted wolffish was the favorite amongst the tannery staff because somehow, this is the Icelandic fish: it lives here, it's tough, it survives and it's ugly (laughs)! There is a saying that the uglier the fish is, the better it tastes.” said Gunnsteinn, fish tannery manager. (Katherine Batliner , Batliner Leather Goods)

Icelandic Wool: A Timeless Legacy of Resourceful Adaptation

Icelandic sheep have evolved to survive on pasture and foliage in the challenging Icelandic landscape. The Iceland sheep today are direct descendants of the sheep imported by early Viking settlers in the 9th and 10th centuries, which are part of the North European short-tailed variety, dominant in Scandinavian and the British Isles during the 8th and 9th century. To keep the breed pure, it is forbidden to import any other sheep breed to Iceland. Icelandic sheep have remained genetically unchanged for over 1,000 years and have a strong immune system due to difficult farming conditions in Iceland. The sheep farming industry offers meat and dairy products, as well as wool as a by-product, showcasing resourcefulness and adaptability in the face of nature's demands.

The Icelandic wool, a historical export, has evolved from a home-based industry to a modern practice. The Icelandic breed is famous for their dual-coated wool, with both inner and outer fibres, providing brilliant protection against the cold in Iceland. Fibers from the external coat are longer, tougher, shiny and waterproof, being built to withstand very low temperatures. Threads from the internal coat are finer, softer and insulating, also providing great protection from the harsh climate. Both fibers can be combined to create a unique wool (Lopi), and used to hand-knit the traditional Icelandic sweaters known as lopapeysa. Lopapeysa can be itchy, but many Icelandic children wear it from birth and are accustomed to its sensation. The spirit of resilience against harsh winters is encapsulate in these woolen sweaters, socks, mittens, blankets and gloves. The domestic crafts of felting, knitting, and tapestry weaving weave a tapestry of Icelandic identity, offering not only functional products but also psychological solace during the extended winter months.

Icelandic sheep have evolved to survive on pasture and foliage in the challenging Icelandic landscape. The Iceland sheep today are direct descendants of the sheep imported by early Viking settlers in the 9th and 10th centuries, which are part of the North European short-tailed variety, dominant in Scandinavian and the British Isles during the 8th and 9th century. To keep the breed pure, it is forbidden to import any other sheep breed to Iceland. Icelandic sheep have remained genetically unchanged for over 1,000 years and have a strong immune system due to difficult farming conditions in Iceland. The sheep farming industry offers meat and dairy products, as well as wool as a by-product, showcasing resourcefulness and adaptability in the face of nature's demands.

The Icelandic wool, a historical export, has evolved from a home-based industry to a modern practice. The Icelandic breed is famous for their dual-coated wool, with both inner and outer fibres, providing brilliant protection against the cold in Iceland. Fibers from the external coat are longer, tougher, shiny and waterproof, being built to withstand very low temperatures. Threads from the internal coat are finer, softer and insulating, also providing great protection from the harsh climate. Both fibers can be combined to create a unique wool (Lopi), and used to hand-knit the traditional Icelandic sweaters known as lopapeysa. Lopapeysa can be itchy, but many Icelandic children wear it from birth and are accustomed to its sensation. The spirit of resilience against harsh winters is encapsulate in these woolen sweaters, socks, mittens, blankets and gloves. The domestic crafts of felting, knitting, and tapestry weaving weave a tapestry of Icelandic identity, offering not only functional products but also psychological solace during the extended winter months.

|

“People have an idea that weaving is calming – that the act of weaving is your heartbeat heard in the ‘click click click’ of the loom,” – this click being the rhythmic sound once produced by river stones hung from the warp-weighted looms for tension. The stones themselves were precious because they had natural water-worn holes through the middle and were only found in the highlands.” Textile artist and educator Ragnheiður Þórsdóttir

|

A Rhythmic Connection to the Past

“It is important to keep traditions for future generations,” said Aðalheiður Margrét Gunnarsdóttir, a teacher in classical singing and local opera performer who lives in Fljótshlíð.

The Icelandic crafts reflect a profound connection to nature and the rhythms of the seasons, embodying qualities of integrity, resilience, and enduring spirit. Rooted in tradition, these crafts seamlessly bridge the past and present, remaining relevant in modern times. Fish tanning and Icelandic wool traditions stand as living testaments to a culture deeply intertwined with nature's offerings, showcasing resourcefulness, sustainability, and a harmonious coexistence between people and the environment. Through this fusion of heritage and innovation, Icelanders cultivate a legacy marked by respect for nature, upholding their vibrant cultural heritage with unwavering dedication.